Reuniting abroad

Jenniffer Perez Lopez barely remembers the small Guatemalan village where she lived until she was 5 years old. In the two decades since her parents brought her to the U.S., her grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins receded into memory, reduced to social media friends. Like millions of others who crossed the border as children without documentation, federal law made it impossible for her to travel abroad or visit her extended family.

But now, as a graduate student in sociology at UCI’s School of Social Sciences, Perez

Lopez has been able to travel abroad for research – and also reunite with her extended

family – through a program organized by Laura E. Enriquez, UCI associate professor

of Chicano/Latino studies.

But now, as a graduate student in sociology at UCI’s School of Social Sciences, Perez

Lopez has been able to travel abroad for research – and also reunite with her extended

family – through a program organized by Laura E. Enriquez, UCI associate professor

of Chicano/Latino studies.

“You basically have to pack a whole lifetime into a week,” says Perez Lopez. “But it was like finally getting an entire sense of self, of finding missing pieces.”

Enriquez organized a trip to Mexico over winter break for 35 UC students and researchers, including 18 UCI students who took Enriquez's fall quarter course on undocumented immigrant experiences. This trip – the fourth Enriquez has organized – is funded by a $50,000 grant from UC Alianza MX, a systemwide initiative that supports cross-border research.

Building Binational Bridges

These international educational opportunities are part of the Building Binational Bridges program, and are organized in collaboration with the UCI DREAM Center, and supported by the Office of Scholarships and Financial Aid, UCI Study Abroad Center, the Center for Educational Partnerships, and other campus resources. While Enriquez takes groups to Mexico, a handful of students like Perez Lopez have simultaneously undertaken research trips to Central American countries where they were born and conducted parallel research projects.

While in Mexico, the students and researchers participate in a convening that includes sessions with Otros Dreams en Acción, creating individual and collective artwork, meeting individuals who were deported or returned, and exploring how international mobility impacts individuals’ identities and feelings of belonging. They also conduct autoethnographic fieldwork documenting their experiences before, during and after the trips. The program was recently recognized as a finalist for The Forum on Education Abroad’s Award for Excellence in Education Abroad Curriculum Design.

For most of the travelers, the experience is not only educational, but deeply personal. Many have received Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, a federal program that grants limited rights to young people brought to the country when they were children. The trips primarily provide educational research opportunities, but with major side benefits. DACA recipients can request what’s called “advance parole,” in which the federal government grants them permission to leave the U.S. under certain circumstances, and return legally. Crossing the border in this way, so that they have re-entered the country with federal permission, can be helpful later when they apply to change their immigration status or become citizens.

Traveling abroad not only gives young people the opportunity to experience language and cultures from the country they were born in, but also to reconnect with loved ones.

“There’s a lot of trauma with family separation, and not just separation from parents. People mourn the loss of connection and relationship with extended family, as well,” says Enriquez. “These trips are an opportunity to reconnect with family, and that is really powerful.”

Solving family mysteries

Perez Lopez’s dissertation research aims to explore how young adults rebuild their families through advance parole and international travel. She interviews many of the students upon their return from abroad and collects their written field notes chronicling their feelings about the experience.

Isabel* had a scar from when she was a toddler in Mexico, but none of her family in the U.S. knew how she got it. When she returned to Mexico earlier this year, she met the cousin who had been at her side when she stumbled and got hurt, who filled in the missing pieces of the story.

“She described going on the trip as a growing pain – an experience that brought a lot of pain, but also peace,” explains Perez Lopez.

Maria* was 3 years old when she left her family in Mexico, believing she was going on a vacation to the U.S. She promised her aunt she would bring her candy when she got back. Returning as a young adult, Maria eased her own anxiety about the reunion and helped break the ice by returning to her aunt with a container of chocolate covered almonds from Costco.

Sofia* recounted sharing a meal at her uncle’s favorite taco stand, and the bittersweet realization that she had this wonderful uncle who loved her, and yet had missed out on years of having him in her life.

“Often they realize they have this other family, and they had no idea the connection would be so strong,” says Perez Lopez. “They talk about wanting to keep that connection alive and hoping to go back again.”

On her first trip back to Guatemala, Perez Lopez discovered that her grandmother had photos of Perez Lopez in every room of the house, including baby pictures she had never seen. For two years while her parents built a life in the U.S., she had been raised by her grandparents. Perez Lopez felt embraced and welcomed by extended family members who had known her as a toddler and were proud of the young woman she’d become.

New questions

Traveling abroad to meet long-lost relatives can be an emotional and unsettling experience for many reasons. As the faculty member helping to organize these trips, Enriquez strives to create space for participants to process their experiences through poetry, collage art and writing.

“There’s a lot of healing that they do,” Enriquez says. “But the trip also opens new questions: what are you missing, or how might your life have been different? Often, they are questioning where they belong.”

That question of belonging is one that Enriquez knows all too well. Born in the U.S. to a Mexican father and a White mother, Enriquez did not speak Spanish growing up, and was often viewed as “not Latina enough.” This added a layer of complexity to her own visits to Mexico. Although she could cross the border freely, she had close family members who had previously had undocumented immigration status, and understood first-hand the challenges that creates within a family.

Because of this, she felt it was important to invite UCI students who are U.S. citizens but still feel the impacts of immigration laws through their loved ones, to participate in the trips, as well. Earlier this year, she brought her own two children to Mexico to meet their great grandmother for the first time.

“This program has created an opportunity for me to heal alongside my students – an opportunity I would not have found for myself had I not been engaging in this work with students,” Enriquez says. “But I recognize there is a lot of responsibility in creating these spaces for students grappling with these issues.”

Next steps

For Perez Lopez, one of the hardest moments of the trip came at U.S. Customs & Border Protection at the airport when she reentered the U.S. Both UC immigration lawyers and Enriquez try to prepare the participants for the range of scenarios and emotions they may encounter as they return to California.

“Dr. Enriquez talked to me about the feelings that people experience, and that was really helpful because I don’t think you really realize how you’re going to feel when you’re there,” says Perez Lopez. “It was really heavy coming back. I had the anxiety of, ‘What if they don’t let me in? What would happen to me?’”

On her first trip, Perez Lopez was prepared to be taken into a separate waiting room and asked questions. She texted updates to the UC immigration lawyer as she progressed through the re-entry process. But on her second trip, accompanied by her three siblings who have U.S. passports, re-entry was a breeze.

Being legally admitted to the U.S. on advance parole helps young people if they later adjust their immigration status, usually due to marriage or a special work visa through an employer. But the entire system exists amid uncertainty. The federal DACA program is no longer accepting new applications, closing that potential pathway to citizenship for young immigrants, and ongoing court cases make its future unclear.

“It’s a lot of unknowns for me, and that’s the hard part,” Perez Lopez says. “What’s the next step now?”

For now, Perez Lopez is collaborating with Enriquez on a project, Rewriting Migration Stories, and will analyze the new autoethnographic data collected by students this winter. Enriquez is also working to uplift the best practices she and her collaborators have developed through these four trips. Meanwhile, the UCI DREAM Center is expanding the program to include travel to Japan, which has accessible immigration policies that might allow undocumented immigrants to meet up with family members from China, Korea or the Pacific Islands.

“There’s been a lot of times it’s been hard to do my Ph.D. while being undocumented and being a woman of color, but Dr. Enriquez generally created such a strong space for me,” says Perez Lopez. “I genuinely think I would never have gone back to Guatemala if it wasn't for her help, talking to me about it, encouraging me, and preparing me. I am eternally grateful to her for that.”

Having re-established relationships with her extended family in Guatemala, Perez Lopez talks to her grandfather on the phone every week. And she says it’s been beautiful to read and hear about the stories of her fellow travelers on their journeys to reconnect with families, even as their stories – and hers – continue unfolding.

-Christine Byrd for UCI Social Sciences

* Pseudonym used to protect identity.

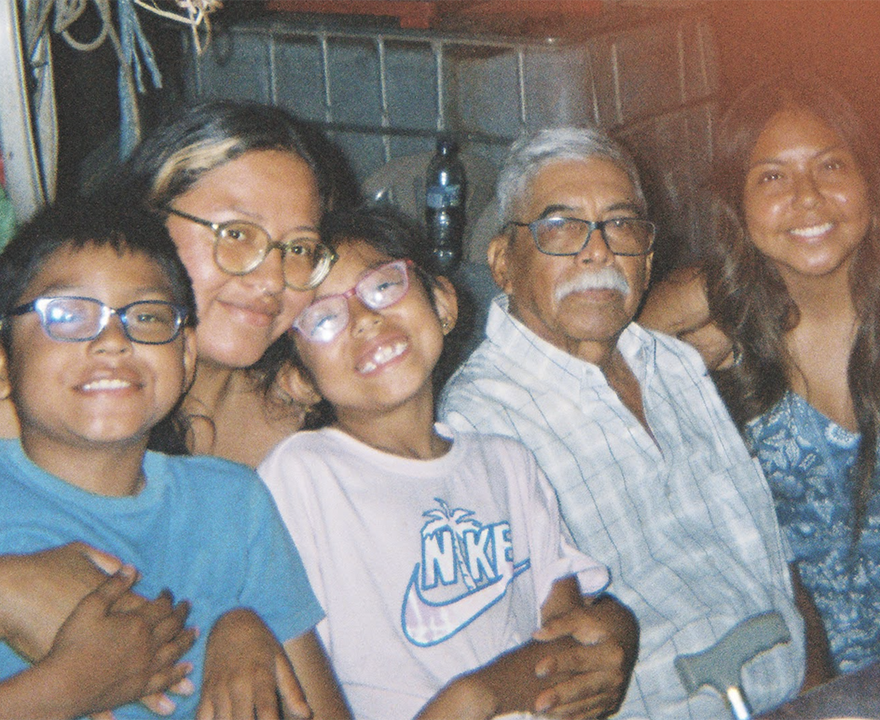

-pictured: Jenniffer Perez Lopez in Guatemala with her family.

Learn more about the UCI Building Binational Bridges Program:

connect with us: