Deadly Decision in Beijing

Deadly Decision in Beijing

- March 2, 2023

- Book by UCI sociologist Yang Su dives into succession politics, protest repression, and the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre from a new perspective

In his new book Deadly Decision in Beijing: Succession Politics, Protest Repression, and the 1989

Tiananmen Massacre (Cambridge University Press) – lauded as a “major contribution” and “page-turner”

by social movement scholars and China experts – UCI sociology professor Yang Su takes

on another major historical event in communist China. Unsatisfied with a literature

that focuses on social protest itself for understanding state repression, he delves

into elite politics, made possible by the historical materials he gathered since his

own participation in the Tiananmen Square Movement in 1989.

In his new book Deadly Decision in Beijing: Succession Politics, Protest Repression, and the 1989

Tiananmen Massacre (Cambridge University Press) – lauded as a “major contribution” and “page-turner”

by social movement scholars and China experts – UCI sociology professor Yang Su takes

on another major historical event in communist China. Unsatisfied with a literature

that focuses on social protest itself for understanding state repression, he delves

into elite politics, made possible by the historical materials he gathered since his

own participation in the Tiananmen Square Movement in 1989.

Q: The Tiananmen Square Movement in 1989 is a landmark event in history for sure, but for older readers who watched it unfold in real time with live TV, and have since read a great deal more, what is new in your book for them?

A: Most people, including scholars, may remember the spectacular display of “people power,” which held the grip of international attention for two months, as well as its abrupt end in bloodshed. As such, Tiananmen has been believed to be a revolution that was cut short. The flipside of it is that the regime could have collapsed, and power changed hands, as happened to other communist countries in East Europe, had it not been for the military suppression. My book, Deadly Decision in Beijing, challenges all of that.

Using historical data, I attempt to adjudicate the merits of the popular view, or what I call a “revolution-suppression model.” A three-way model of succession politics is a much better fit. The leaders did not so much strive to end the protest as they busily took advantage of opportunities presented by the protest. The central concern at the time was the issue of succession - who should succeed the 85-year-old supreme leader Deng Xiaoping and what that would mean for China. I present a narrative in nine chapters to make that point, covering the events leading to 1989, the elite deliberation during Tiananmen, the martial law and its implementation, and the political impact of Tiananmen.

Q: So, if not for ending a revolution, what was the reason for Deng to send in the troops?

Under a closer examination, the student movement was a far cry from a revolution capable of toppling the regime. I agree with historian Jeremy Brown that the movement could have died out without calling in the troops. Indeed, the leaders including Deng knew this much. Deng had once said that student protests “would not end up with much,” and at the height of the 1989 crisis, he privately reassured his listener: “A good economy sets a foundation. ...Now [with this foundation], there is no unrest among the peasants across the nation; nor among the workers, by and large.”

But Deng was nonetheless in political trouble in 1989 with his reform policy at stake. The outbreak of the student movement had just compounded his succession plan. In a three-way contention he needed to fight two fronts. On one, he was sacrificing the then “Crowned Prince,” General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, who had already possessed considerable powers and resisted. On the other, he was fending off his revolutionary peers, the conservative elderly who could install an anti-reform leader in Zhao’s stead. By using martial law and demonstrating his military might, the semi-retired supreme leader reasserted his power and prevailed.

Q: It does sound refreshing to older readers who thought they have already known a great deal. How about younger readers who have grown up witnessing China become a rich country and global powerhouse? Is the history of Tiananmen a thing of the past? Or is there relevance today?

A: With China’s return to strongman politics in recent years, many younger readers must feel a sense disquiet and urgency like their elders, wouldn’t they? Once again and not far away from the future, an aged supreme leader will become a reality.

Beneath its narrative of elite conflict, a major motif of this book is to understand political power transition in the communist system. And this issue is of paramount importance, just like election is for a democratic country. There are poignant lessons to be learned from Tiananmen and other historical events. Deng’s need to dispose his heir apparent in 1989 was reminiscent of the “Crowned Prince Problem” that has bedeviled autocrats of all stripes. My three-way model was inspired by the pattern of a “Triad” documented by scholars of Soviet Union politics. Indeed, uncanny parallels can be drawn between the history of power successions from Lenin to Stalin, Khrushchev, and to Brezhnev and the experiences in China with Mao, Hua, Deng, Zhao, and Jiang.

One lesson is about the likely advent of a political crisis in combination of elite dispute on power succession, popular mobilization, and military intervention. China has been visited by such moments repeatedly in the past, including the Cultural Revolution, the elite struggle and popular protest following Mao’s death, and the Tiananmen. Now with term limits dismantled, a quieter interlude in China’s politics seems to be ending. “The specter of the next Tiananmen may well lurk on the horizon,” I write in my concluding sentence of the book.

Q: What can your book teach us about politics and protests elsewhere? Your reviewers laud your new book as one of the first to focus on “the repressors” to understand the dynamics of protest repression. Why is that angle new and important?

A: It is difficult to study protest repression due to the lack of data on state actors’ decision-making process. As a result, the existing literature is unsatisfying. A common approach puts the focus on the ebb and flow of the protest, and the argument is almost tautological. If repression is harsh, such a model goes, it must be because the challenge is severe, and so on. The above-mentioned “revolution-suppression model” on Tiananmen bears the hallmark of this approach. I am lucky to have access to historical data to sort out exactly what was said and done within the government. This change of perspective allows me to ascertain the real source of the decisions to repress or not to.

To be clear, I am by no means among the first to examine elite politics to understand social protest. There are legions of studies and models doing just that, mostly under the rubric of the “political opportunity structure.” What I depart from such existing work is this: instead of treating elite politics as “opportunities” for protesters, I see protest as a resource for the elite in their own conflict.

Q: How did you get your hands on materials that enabled you to craft this behind-the-scenes narrative of elite political decisions that led to military mobilization in Tiananmen?

A: This book benefited from an unusual amount of material that has accumulated since the Tiananmen Square movement. With thousands of innocent lives lost, the gravity of the tragic event inspired intense public interest and gave rise to a small industry of information gathering and publishing. Among the wide range of contributors are China’s former party general secretary, a former premier, many former officials who were privy to government dossiers, and numerous journalists and independent researchers. This richness of materials allowed me to present a detailed account of elite contentions taking place inside government compounds.

Q: From your last award-winning book on the Cultural Revolution to this new book on the Tiananmen Massacre, is there an underlying theme in your work?

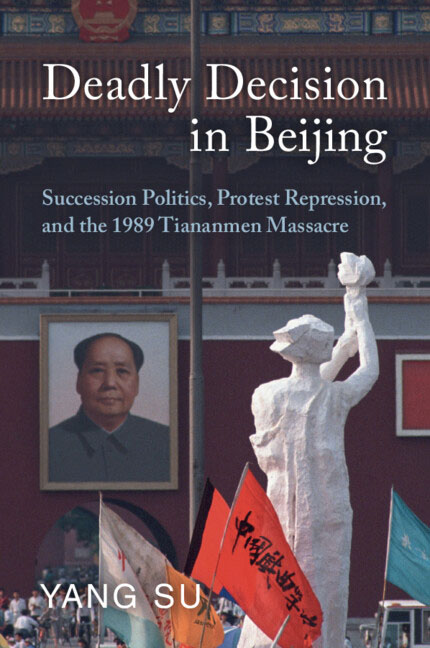

A: Incidentally, the cover of each book contains an image of Mao. If my previous book on China’s Cultural Revolution was about human sufferings inflicted by Maoism, this new book, in a sense, is about a cast of characters working hard to move China away from that monstrous system. Those efforts include Deng’s reform on the government’s side and the pro-democracy movements on society’s side. Much has changed in China since then, and in retrospect the work of those people now looks even more valuable. I see many of them as my heroes. In an opening page of the book, I quoted a passage from Moby-Dick to express my underlying intentions: “I, Ishmael, was one of that crew; my shouts had gone up with the rest; my oath had been welded with theirs; and stronger I shouted, and more did I hammer and clinch my oath, because of the dread in my soul. ... With greedy ears I learned the history of that murderous monster.”

Yang Su is a professor of sociology in the School of Social Sciences at UCI. His last book, Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution, also published by Cambridge University Press, was the 2012 winner of Barrington Moore Book Prize of the American Sociological Association.

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on:

connect with us: