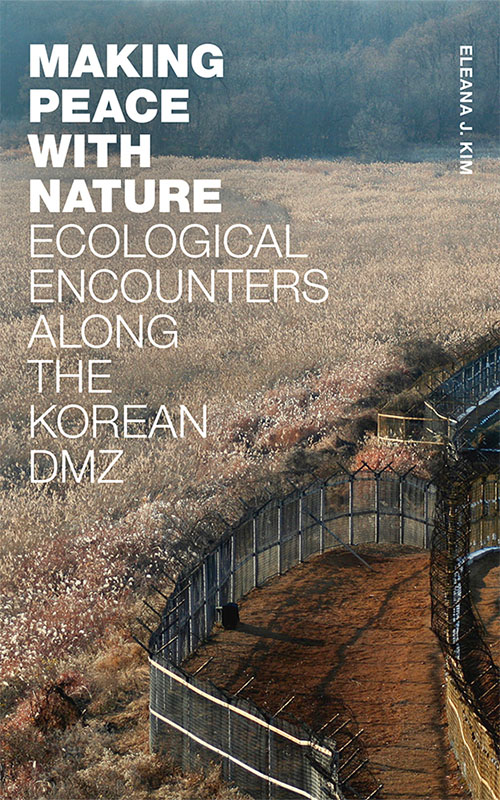

Making Peace with Nature: Ecological Encounters Along the Korean DMZ

Making Peace with Nature: Ecological Encounters Along the Korean DMZ

- November 16, 2022

- Book by Eleana Kim, UCI anthropology professor, explores how nature has flourished where human diplomacy has failed

In her newest book, Making Peace with Nature: Ecological Encounters Along the Korean DMZ (Duke University Press), UCI anthropologist Eleana Kim draws on ethnographic fieldwork

to explain how human and nonhuman ecologies interact and transform in spaces defined

by war and militarization. Below, she gives a brief history of the zone’s nearly seventy-year

existence and how, amid the context of climate crisis, perpetual wars, and ongoing

militarization of the planet, the area can serve as a framework for conceptualizing

peace beyond human geopolitics.

In her newest book, Making Peace with Nature: Ecological Encounters Along the Korean DMZ (Duke University Press), UCI anthropologist Eleana Kim draws on ethnographic fieldwork

to explain how human and nonhuman ecologies interact and transform in spaces defined

by war and militarization. Below, she gives a brief history of the zone’s nearly seventy-year

existence and how, amid the context of climate crisis, perpetual wars, and ongoing

militarization of the planet, the area can serve as a framework for conceptualizing

peace beyond human geopolitics.

Your previous work focused on transnational adoption from South Korea. What prompted your shift to examine nonhuman life in the DMZ?

My first book, Adopted Territory: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Politics of Belonging (Duke University Press, 2010), analyzed the social and political emergence of a global network of adult adopted Koreans. Shifting my focus to the Korean Demilitarized Zone and the status of the DMZ as a haven for biodiversity was, in many ways, a radical departure. But there are some threads common to both adoption and the DMZ: They emerged directly out of the Korean War, and the cultural meanings and values of each have been deeply affected by the Cold War and US empire. Furthermore, and conceptually, both topics are related to an anthropological fascination with boundaries and borderlands, particularly the ones humans create between what is supposedly “natural” and what is supposedly “cultural.” In the case of adoption, presuppositions and contradictions regarding kinship as being something that is deeply “natural” and yet that is also socially constructed come strongly out into relief. This is very much the case when it comes to transnational, transracial adoption, in which questions of “nature and nurture” continue to loom large—and are further complicated by discourses of race and nation. When we think of the DMZ, it is a space that is defined by human history and geopolitics, yet, because of this exceptional political status, it is also a hybrid naturalcultural borderland defined by its rare biodiversity.

Give us a Cliffs Notes version of how the DMZ is governed and who is allowed to do what where.

The Korean Demilitarized Zone, or DMZ, was established with the signing of the 1953 Armistice Agreement, which suspended, but did not end the Korean War. The Korean War began in June 1950, and the armistice was signed in July 1953. The military demarcation line, or MDL, constitutes the “border” where the front lines were located at the agreement’s signing. The DMZ is demarcated by the Northern Limit Line and the Southern Limit Line, which lie two kilometers north and south of the MDL. In that 4-kilometer wide space, no heavy artillery is allowed. The southern part of the DMZ is governed by the UNCMAC, or United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission, and the northern part is governed by the DPRK army. Part of the enmity between the two Koreas has to do with the fact that both states consider themselves to be the rightful sovereign of the entire Korean nation, and as such, both consider the DMZ to be part of their territory. When it comes to the southern side, however, South Korea has no sovereignty over the two-kilometer-wide strip on their side of the MDL. What is important for understanding the biodiversity of the DMZ is that the majority of ecological research has taken place in what is known as the DMZ region, which encompasses the area immediately south of the Southern Limit Line, which includes the Civilian Control Zone, or CCZ, and the Border Area. The CCZ and the Border Area are where all the weapons, battalions, barracks, shooting ranges, and military bases are located. The intense fortification and guarding of these areas are what make the DMZ among the most heavily militarized areas in the world.

Given the area’s divisive history, how has nature flourished where human diplomacy failed?

Nature in the DMZ is far from pristine, but it is relatively protected, given the restrictions on human habitation forced by the Armistice Agreement and the ongoing state of division and war. Some of the contaminating aspects of the ecologies there include landmines and unexploded ordnance, frequent fires, and unregulated military waste and effluvia. And the area is also the site of agricultural and industrial activity, as well as security tourism and ecotourism. The attention to the DMZ’s status as an accidental sanctuary for biodiverse forms of life began in the 1960s and endangered species, including the red-crowned crane and amur goral, among many others, have continued to captivate the imagination of people in the Koreas and across the world. How this fact has evolved in relation to South Korean politics, the division of Korea, and the ongoing war is something I examine in my book—that “nature” has helped South Koreans to rethink the meanings of division and to invest some hope in the ability of nature to “heal the scars of division,” as many popular discourses suggest, even as the political enmity between the two Koreas has continued and intensified well beyond the end of the Cold War.

What lessons can we learn from the rich biological peace you found there?

In contrast to prevalent narratives in South Korea and internationally that attempt to locate hope and peace through the symbolic appropriation of the DMZ’s nature, my book ethnographically analyzes actually existing relations of humans and nonhumans in the CCZ areas of South Korea. I borrow the notion of biological peace from one of my key interlocutors, Director Kim Seung Ho of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. Kim and his colleagues regularly monitor and study the biota of the area around the Han River Estuary, on the western side of the DMZ area. My book analyzes the multispecies relations made possible by small irrigation ponds, migratory birds, and landmines to foreground this idea. Especially in the context of the climate crisis, perpetual wars, and ongoing militarization of the planet, we need frameworks for conceptualizing peace beyond human geopolitics. In my framing, biological peace does not merely look to the natural world for analogies to emulate or models of cooperation in nonhuman societies, but it draws attention to the necessary work of nurturing and enacting ethical relations of care in worlds marked by industrial pollution and military violence.

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on:

connect with us: