Bridging a gap

In the decade since graduating from UCI’s School of Social Sciences, Dana Ballout ’08 has been a journalist, documentary filmmaker, and radio producer.

She’s lived in Beirut, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. Wherever she goes,

she tells stories of everyday heroes facing harrowing experiences - from war to sexual

abuse.

In the decade since graduating from UCI’s School of Social Sciences, Dana Ballout ’08 has been a journalist, documentary filmmaker, and radio producer.

She’s lived in Beirut, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. Wherever she goes,

she tells stories of everyday heroes facing harrowing experiences - from war to sexual

abuse.

“I gravitate toward these stories,” she says, “and I think it’s important to tell these stories.”

Recently, millions of NPR listeners heard Ballout tell one such story on “This American Life,” about Syrian radio host and activist Raed Fares who was assassinated late last year.

“Dana has worked really hard, taken risks, and even worked when not being paid for a while,” says Daniel Wehrenfennig, executive director of the Olive Tree Initiative, who has known Ballout since she was a student. “You can do a lot when you’re passionate enough about what you do, and willing to take risks.”

East and West

Born in California, Ballout spent most of her childhood in post-war Lebanon, sometimes surrounded by conflict, before following her older brother to UCI in 2005. She was drawn to political science and international studies courses for her major, but much of her learning took place outside of the classroom.

“UCI gave me the chance to be part of something larger than my classes,” says Ballout.

As an undergraduate, Ballout lobbied campus officials to start a Middle East studies minor and served as president of the Model United Nations. Her most lasting impact, though, was co-founding the Olive Tree Initiative, which gave students the opportunity to travel to Israel and Palestine and meet people whose daily lives were affected by the conflict. More than 600 students have participated in the program over the last 11 years.

“I wanted others to see what the conflict really looked like,” says Ballout. “I think

it’s important that people look in the face of what they think is the ‘enemy.’”

“I wanted others to see what the conflict really looked like,” says Ballout. “I think

it’s important that people look in the face of what they think is the ‘enemy.’”

When she graduated from UCI in 2008, Ballout returned to Beirut to put her international studies degree to work for the United Nations Development Program. As a wave of anti-government sentiment bubbled up in Lebanon, Ballout photographed anti-sectarian protests demanding political reform in Beirut. Eventually, at the encouragement of a mentor and friend, she was inspired to go to journalism school.

With a full scholarship to Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, Ballout moved to Chicago - even though she had never even visited the city before. There, she had the opportunity to practice her reporting skills covering local political heavyweights like mayor Rahm Emanuel.

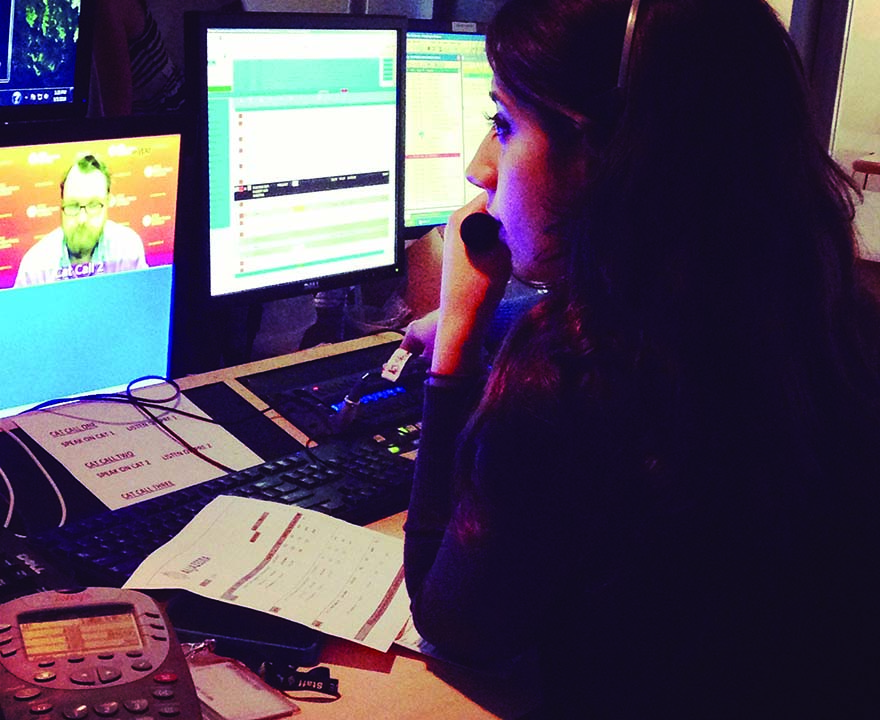

When she completed the year-long master’s, Ballout moved to Washington, D.C., and interned for Agence France-Presse and Al Jazeera English, before becoming a producer for the newly created Al Jazeera America when the station launched in 2013.

“TV is a very powerful tool, if you have the right audience,” says Ballout. “Unfortunately, the people watching Al Jazeera America were the ones who were already educated on the issues.”

Before Al Jazeera America closed down for good, Ballout once again returned to Lebanon. The progressively violent Syrian war was drawing increased international intervention, and Ballout was hired to cover the conflict by the Wall Street Journal - the pinnacle of print journalism.

On any given day, she might travel to Lebanon’s countless informal Syrian refugee camps or be on the phone with civilians who were living under siege, their families starving as bombs exploded overhead. But Ballout says she was never the type of reporter to crave an adrenaline rush.

“There were moments when I was asking myself, what am I doing here?” she says. “One minute I’m talking to a person and the next minute they’re dead, or I would wake up with photos of dead children on my phone that people have sent.”

Raed Fares, who would eventually become the subject of Ballout’s segment on “This

American Life,” was one of the sources Ballout would check in with periodically.

Raed Fares, who would eventually become the subject of Ballout’s segment on “This

American Life,” was one of the sources Ballout would check in with periodically.

At one point, Ballout was making her morning phone calls to her sources, asking how many women and children had died in bombings the night before.

“It was as if someone were telling me what they ate for breakfast,” she says. Tragedy had become routine.

Emotionally drained, Ballout quit her job and returned to Southern California, where her sister had just given birth. She hoped the attention on the new baby would be personally renewing.

Back in Los Angeles, Ballout produced podcasts for the Middle East-focused “Kerning Cultures,” and joined the production team for a Netflix show.

“In my overall desire to tell stories and make an impact, I keep trying to find the medium that would be the most powerful form of storytelling,” she says.

Being a bridge

At the end of 2018, Syrian radio host and activist Raed Fares was murdered. Although

Ballout had never met him in person, the news profoundly upset her. Fares had founded

Radio Fresh, a community radio station that promotes ideas of equality and democracy,

and covers hyperlocal news in a war-torn region of Syria - including broadcasting

warnings about incoming air strikes.

As extremist Islamist groups took control of the region, officials insisted Radio Fresh stop playing music and allowing women on the radio. Fares’ responses were subversive: the station played sounds of tweeting birds and bleating goats instead of music, and modified female reporters’ voices with computer software to sound less feminine.

The station is now in danger of shutting down, not because Fares is gone, but because the U.S. has pulled funding.

Ballout was trying to place a story about Fares and Radio Fresh in mainstream American media when “This American Life” reached out to “Kerning Cultures.” Ballout was soon reporting, helping produce, and eventually narrating the 22-minute segment, “Good Morning, Kafranbel.” As a long-time listener and huge fan, the opportunity was one of the most exciting moments in her career.

The radio show, hosted by Ira Glass, is heard by 2.2 million listeners on 500 radio stations each week, and the podcast version gets downloaded by another 2.5 million listeners. For one week, Ballout worked in the show’s New York office, collaborating with Glass and the rest of the team.

“The ‘This American Life’ producer Diane Wu was so good at helping to tell the story in a way that was human and relatable,” Ballout says. “I find that so many stories around Syria often are not told with the dignity that they deserve, but she let me tell the story with dignity.”

This included letting clips of an Arabic speaker’s voice finish a complete sentence before the translator’s voice broke in, and keeping in a joke about a rural Syrian accent that would be lost on English-speaking listeners. Actually, Ballout was impressed that “This American Life” was interested in telling Fares’ story at all.

“People don’t want to hear about the Syrian war anymore,” says Ballout. “But Ira Glass told me that sometimes you have to trick people into caring about stories that matter. You start off making it relatable by framing it as a story about community radio, something people relate to and then all of a sudden - bam! - you’re in a Syrian war zone. By then listeners are already in too deep.”

Ballout says the entire process was not only professionally invigorating, but emotionally healing for her.

“The reason Dana is so good at what she does is her empathy, that she really cares for her subject,” Wehrenfennig says. “She tells stories of normal people doing something heroic, and those stories share part of a larger truth.”

“And as a woman from the Middle East, Dana can be a bridge between that part of the world to Western and American audiences,” he adds.

Later this year, audiences will have another opportunity to experience Ballout’s work, with the release of the independent film “Groomed,” about how sexual predators groom their victims, establishing an emotional connection before beginning the abuse. As a co-producer on the movie, Ballout had to meet and interview a convicted child molester.

While the subject matter is deeply disturbing, Ballout insists it’s important for people to look in the eye of the “enemy” and, while not to sympathize, to humanize them. Ballout even manages to find beauty in human perseverance she witnesses.

“It always inspires me in ways that make me so grateful,” she says. “In the midst of all these traumas, there are pockets of human resilience. That’s what’s amazing to me. There is beauty in all of them.”

- Christine Byrd for the UCI School of Social Sciences

Follow Dana’s journey online:

Website: www.danaballout.com

Twitter: https://twitter.com/balloutd

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/danaballout/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/danaballout/

FB: https://www.facebook.com/dana.ballout

connect with us: