Human rights best practices

Human rights best practices

- February 13, 2009

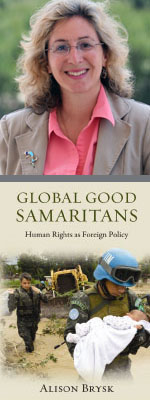

- Political scientist Alison Brysk examines international human rights success stories in new book, Global Good Samaritans

-----

President Obama's signing of executive orders to close the Guantanamo Bay detention

facility and limit interrogation techniques in U.S. facilities worldwide is a big

step forward for what has been a lagging overall national policy on international

human rights, says Alison Brysk. A UCI political science professor who specializes

in human rights research, she is the author of Global Good Samaritans, a new book

in which she provides a comparative look at human rights foreign policy best practices

abroad.

President Obama's signing of executive orders to close the Guantanamo Bay detention

facility and limit interrogation techniques in U.S. facilities worldwide is a big

step forward for what has been a lagging overall national policy on international

human rights, says Alison Brysk. A UCI political science professor who specializes

in human rights research, she is the author of Global Good Samaritans, a new book

in which she provides a comparative look at human rights foreign policy best practices

abroad.

"As the United States begins to reexamine its policies, there are a number of good

role models throughout the world with impressive records of being active human rights

promoters from whom we could learn a few lessons," she says.

Over the span of five years, she conducted research in six different countries including

Canada, Sweden, the Netherlands, Costa Rica, South Africa and Japan where she studied

their records of "global citizenship" or support for United Nations related work,

bilateral diplomacy, peace promotion, international humanitarian assistance and refugee

reception.

"Each of these policy areas make a marked difference in a country's ability to put

policy and standards into practice on the ground," she says.

Her broad research included in-depth reviews of written policies and interviews with

officials in government, foreign ministries, non-governmental organizations and humanitarian

programs.

Her findings put Canada at the top of the list for human rights policy role models

due to their success at "building up international institutions, harnessing promotion

of human rights and democracy to global alliances and providing higher level of foreign

aid toward the constructive empowerment of local populations." Detailed further in

the book, she also notes the country's compassion toward refugees and support for

the International Criminal Court as being critical to their effective implementation

of international human rights policy.

Among the other countries studied, Brysk highlights key areas in which they have found

success. "Sweden and the Netherlands are known historically as leaders in the human

rights arena for their national approach to global citizenship. Japan, on the other

hand, is not quite there but has aspirations of making international human rights

a national priority."

In the case of South Africa, she tells the story of the country's domestic shift from

apartheid to democracy which "changed them from a regular human rights de-stabilizer

to a force for progress in their troubled region."

"The United States has a historical problem of always wanting to 'go it alone' and

reinvent the wheel," she says. "By learning the lessons of history from the benefit

of international examples, we can begin to revamp our policy toward international

human rights to be more effective and humane."

Her book will be the topic of a reader-meets-author panel at the International Studies

Association's annual meeting Tuesday, February 17 in New York City.

Funding for Brysk's studies on which the book is based included a Fulbright fellowship

and grants from the Social Science Research Council and Abe Foundation.

Global Good Samaritans (Oxford Press)

-----

Would you like to get more involved with the social sciences? Email us at communications@socsci.uci.edu to connect.

Share on:

Related News Items

- Careet RightUCI soc sci spotlight: Beijie Ann Tang

- Careet RightHow a Trump's tariffs are affecting an Orange County matcha shop

- Careet RightNew faculty interview: Crystal Robertson

- Careet RightNew faculty interview: David Inman

- Careet Right7 scientific clues that explain why you're so attractive to some people but not others