A quantum leap forward?

A quantum leap forward?

- October 23, 2009

- LPS professor Jeff Barrett is searching for answers to one of philosophy and physics’ deepest mysteries

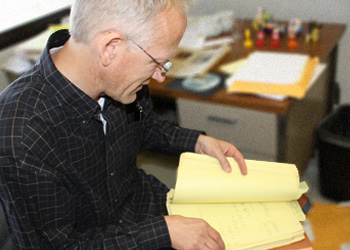

For logic and philosophy of science professor Jeff Barrett, taking delivery of the

dusty old boxes that now line the walls of his UC Irvine office marked a high point

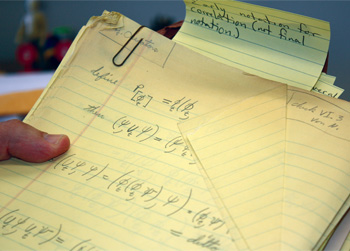

in his academic career. Their contents: pages and pages of handwritten notes, most

more than 50 years old, penned by famous quantum theorist, Hugh Everett, III.

For logic and philosophy of science professor Jeff Barrett, taking delivery of the

dusty old boxes that now line the walls of his UC Irvine office marked a high point

in his academic career. Their contents: pages and pages of handwritten notes, most

more than 50 years old, penned by famous quantum theorist, Hugh Everett, III.

With a newly awarded $160,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Barrett and a team of researchers are combing through, scanning and preserving the documents which they hope may shed light on the quantum measurement problem, one of philosophy and physics’ deepest mysteries.

“Everett liked to debunk things,” says Barrett, author of The Quantum Mechanics of Minds and Worlds, a book about Everett’s work in quantum theory. “He was always the first to say

‘It can’t work like that’ and then he’d work to provide evidence showing that he was

right.”

“Everett liked to debunk things,” says Barrett, author of The Quantum Mechanics of Minds and Worlds, a book about Everett’s work in quantum theory. “He was always the first to say

‘It can’t work like that’ and then he’d work to provide evidence showing that he was

right.”

Everett spent most of his life working as a defense contractor for the Pentagon where he put his Princeton-acquired physics training to use developing game theory simulations for government analysts and policy makers. Based on his theories, policies were developed to solve problems before they were encountered. One such example included his contributions in the 50s to the development of the theory of mutually assured destruction, the notion that if nuclear war was to break out, there would be no survivable options for retaliation.

It was his work as a graduate student, however, that earned him his spot in history books. While pursuing his Ph.D. in physics, he had an idea for a new way of thinking about quantum mechanics, the theory of how objects physically exist.

“The standard formulation of quantum mechanics has two separate rules that explained

how the state of a physical system changed over time: a special rule for when the

system is observed and an ordinary rule for all other times,” says Barrett, explaining

in the most elementary way possible a field of study which continues to perplex and

puzzle some of the most intellectual minds and one that serves as an on-going source

of material for creative science fiction writers and others in the entertainment industry.

“What Everett asked was ‘Why not just use the standard rule all of the time, even

when a system is observed?’”

His resulting dissertation, the only work that Everett would ever wind up publishing,

proposed dumping the special rule and taking the standard rule as universal as a means

for explaining all experience. He called the theory universal wave mechanics, which

later came to be known as the many worlds theory. While it caught some attention

when it was first published, it didn’t gain popularity until the mid 70s. By that

time, says Barrett, Everett had given up on the academic world due in part to the

resistance and skepticism he met when first explaining his work.

Everett passed away in 1982 and his son Mark, lead singer/songwriter of the indie rock band EELS, inherited some of Everett’s belongings.

Fast forward to 2007. In honor of the 50th anniversary of the theory of quantum mechanics, Scientific American commissioned Peter Byrne, journalist, to write a biography of Everett’s life. Byrne went knocking on Mark’s door and stumbled upon the treasure trove in the rock singer’s basement. After some digging, Byrne realized he had everything from Everett’s days as a college student to his personal commentaries on other physicists’ interpretations of Everett’s work.

Byrne contacted Barrett to help him make sense of some of the more technical documents.

“Most physicists would agree with Everett’s proposal to use the standard dynamical

rule for all interactions, including measurements, but exactly how it’s supposed to

work has never been clear and there remains significant disagreement in the interpretation

of his theory,” Barrett says, rattling off nearly half a dozen different views including

the splitting worlds, many histories, and consistent histories formulations; the many

minds interpretation, and most recently, the Oxford formulation of Everett, each of

which have been developed by different physicists or philosophers claiming to have

the best interpretation of Everett’s theory.

“Everett was still alive in the 70s and early 80s when most of these interpretations were being developed. He was reading this stuff and making notes on photocopied articles that are buried in these boxes, writing things in the margins like ‘no, here’s what I meant.’”

While Barrett is hesitant to say that the notes will determine once and for all how to best understand Everett’s theory, he says that it is exciting to see where the exploration might lead.

The history of Everett’s theory reads like a novel, and those interested in learning the rest of the story will soon have the opportunity to do so when Byrne’s forthcoming book with Oxford University Press is released.

For Barrett, the opportunity to sift through the physicist’s notes has provided “a once in a lifetime chance to read something I care very much about but never knew existed.”

“Everett proposed an exciting strategy for solving the quantum measurement problem. Our interest now is in sharing his reflections in the hope that they might help spark further developments and discoveries in philosophy and physics.”

Everett’s notes will be made available online at UC Irvine after scanning has been

completed. The physical documents will be added to the American Institute of Physics’

archive on Everett. Typescripts of the most important work, together with introductory

essays and interpretative notes by Byrne and Barrett, are scheduled to be published

by Princeton University Press in the 2010-11 academic year.

Share on:

connect with us